A year after a huge explosion leveled Beirut’s port, the National Museum has reopened, and its Phoenician timepiece is on display.

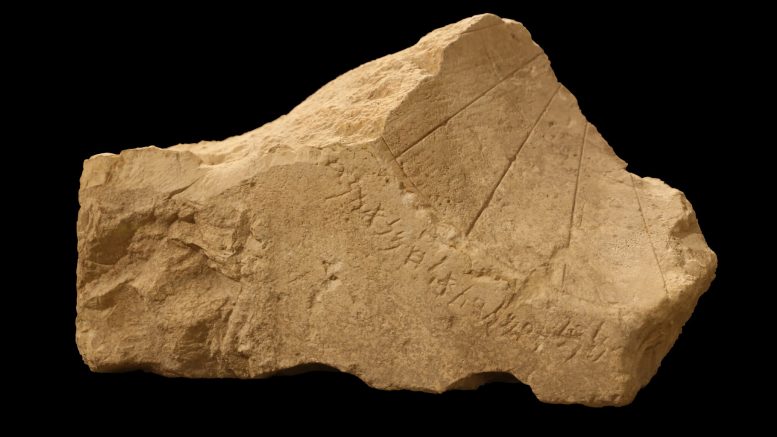

The National Museum of Beirut has only one ancient timepiece: part of a second-century-B.C. sundial. It was broken at some point in the past, but the fragment in the museum has survived even the enormous explosion that leveled the nearby Port of Beirut on Aug. 4, 2020, blowing some of the museum’s doors off their hinges and shattering windows.

The museum reopened on July 1 after a $175,000 restoration, donated by the Aliph Foundation through the Louvre Museum in Paris, and the sundial is once again on view, protected in a glass vitrine.

At a glance, it looks “like a lump of stone,” said Ruth Young, an archaeology professor at the University of Leicester in England, whose specialties include the Middle East. Yet on closer inspection, she noted, “you can see the precision with which the lines are carved, marking out the passage of time.”

The sundial is “a two-part stone,” said Tania Zaven, regional director of the north Mount Lebanon area, which includes the World Heritage site of Byblos, for the Directorate General of Antiquities in Lebanon. “We have one part of the sundial, and the other part is in the Louvre Museum.”

The main corridor of the museum. The institution is open again after undergoing a $175,000 renovation to repair damages caused by the explosion in August 2020.Credit…Diego Cupolo/NurPhoto, via Getty Images

The pieces were found in Umm el-Amed

The pieces were found in Umm el-Amed, in southern Lebanon. When the device was whole, it had 12 lines of identical length incised into it because the Phoenicians, the traders and sailors who first used it, “calculated the shadows, to see what time it is,” Ms. Zaven said.

The piece in the Beirut museum, which, at 12.5 inches high and almost 18 inches wide, is the larger of the two, was found between 1943 and 1945. Its hour markings are “four equal lines and a little bit of the fifth one,” Ms. Zaven said.

The Louvre’s fragment, found circa 1860-61, is smaller and has only two complete hour lines and one broken one.

The rest of the sundial is still missing, including the triangular gnomon, or blade, that casts the shadow so users can discern the hour. But excavations at the site are continuing, and, as Umm el-Amed is close to the Israeli border, access is restricted. “It’s helped preserve it, to be honest, as it doesn’t get many visitors,” Professor Young said.

She added that she would like the two pieces to be reunited and kept at the Beirut museum “because it is Lebanese.”

“It’s from that area, that territory, that place,” she continued, “and I think that artifacts belong in the place where they were found, as closely as possible.”

In Lebanon, she said, while “the French are talking about intervening in some way in the economy and political situation, I think that archaeology and the return of broken sundials is probably going to come quite low down on the list of priorities. But it is something to hope for in our lifetimes.”

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/08/fashion/watches-national-museum-of-beirut-sundial.html

Be the first to comment on "In Lebanon, Part of an Ancient Sundial Returns to View"