By Martin Longley

Fairuz is now 85 years old, still the dominant female singer in Lebanon, and indeed the Arabic world itself. The departed Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum is the only other contender. Fairuz is the Arabic word for “turquoise,” her birth name being Nouhad Haddad. She started out as a radio chorus vocalist, which led to meeting the Rahbani Brothers, Assi and Mansour, who instantly clicked into a songwriting partnership with Fairuz. Assi and Fairuz married in 1955. This personal and professional relationship was sundered in 1979, from which point Fairuz inducted her son Ziad Rahbani as her chief composer and arranger.

In the last 18 months, there have been a pair of Fairuz vinyl LPs released by We Want Sounds, a retro-digging Parisian label that has good taste enough to present classics, or sometimes obscurities, via collectible resuscitations. They’ve reissued old platters by Ennio Morricone, Serge Gainsbourg, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Don Cherry, and Harold Land, as well as having the soundtracks to Serpico and The Friends Of Eddie Coyle amongst their exhumations. We Want Sounds have also released Ziad Rahbani’s Abu Ali album, from 1978.

Many of these WWS albums enjoy the dual nature of possessing innate magisterial qualities and offering a partially ironic lounge exotica aura, which is usually provided by the listener in cahoots with the relentless procession of the decades themselves. It is no negative act to simultaneously appreciate any multiple style aspects, without one consuming the other. We can radiate knowing hipness, and also cast mental self-shapes back to the 1970s, with even a frequently questionable dip into the 1980s being permitted. These revived Fairuz LPs inhabit the time-phase betwixt 1979 and 1984.

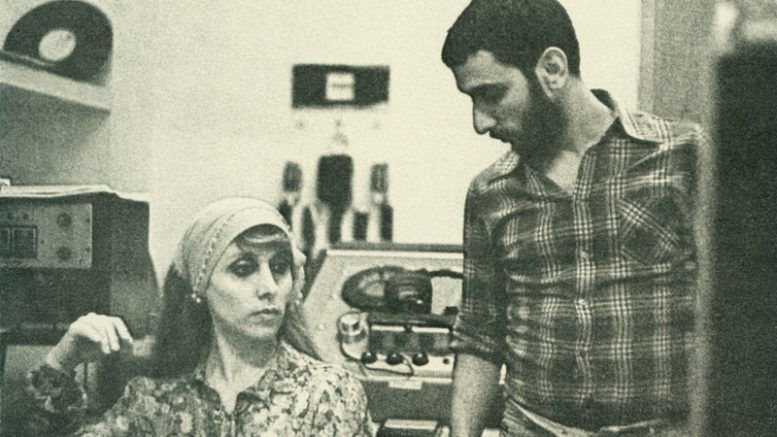

In 1979, Fairuz recorded her Wahdon (‘“Alone”) album in Beirut and Athens, with her son Ziad now swiveling around in the producer’s chair. It perfectly illustrates her move from mainstream Arabic song towards a disco-funk-ballad approach, impregnated by Stateside influences. These natures are conveniently split between side one and side two, composed and arranged by Rahbani, who creates a strong foundation from which his mother’s voice vaults higher and higher.

The first side (recorded in Beirut) features oud, percussion, spreading strings, and a male dominated vocal chorus, following the golden seam of Fairuz’s established traditional style. The second (laid down in Athens) brings in a tougher bass drum kick, electric bass, and a series of warbling synthesizer solos, as if Rahbani sees himself as the cool-gliding Creed Taylor of Beirut.

Fairuz’s voice wafts and flutters with gracefully static lines, adding decorative details in her phrasing. “Baatilak” brings flute and accordion, with its strings echoing Fairuz herself. The following “Ana Indi Haneen” perfectly demonstrates the superbly aligned elements of this LP; even without grasping the Arabic language, we can still drink from Fairuz’s profoundly melancholic draft. The second side’s opening “Al Bosta” delivers sizzle-splash hi-hat and clipping cocktail romance piano, rippling under its glittering disco-ball glare, with the male vocal chorus flipping into female form, Crimplene shapes spinning. Or is that almost a pert medieval prance?

Our modern dance interpretations might demand sly-smile irony-contortions, but the gristle of this newfound bounce retains its integrity. Then, Fairuz is smoochily forlorn on the title cut, spreading charm through a retro-gauze of cinematic drama, a honeyed tenor saxophone responding to her languid lines. In 1979 her long-term followers must have been quite ruffled by this radical shift in style.

The freshly issued Maarifti Feek, also on WWS “deluxe edition” vinyl, explores a similar marriage of some differing ingredients. In 1984, Fairuz is still found pushing away from her mainline, established style, doubtless influenced by her son’s musical direction. Once again, this album features a duality of approach, its first six tracks suffering in their attempts to include jazz lounge flourishes. There are clumsy electro-drum spurts, tinny keyboards, seductive trumpet, worming Moog and bland backing vocals, with Fairuz a touch too low in the mix.

In the middle there’s “Le Beirut,” a puzzling variation on Joaquin Rodrigo’s Concierto de Aranjuez. It’s the last four cuts that inspire as the direction that most suits Fairuz’s voice and demeanor, sounding as if they were recorded at a different session, with different musicians, resulting in a tighter, dynamic energy. The instrumental “Entowrah” is rhythmically taut, with a rattling goblet drum, and keyboards that sound closer to a 1980s Algerian raï earthiness. Fairuz has a more windswept, minimalist setting for “Ma Kedert Neseet”, and the old morose nature makes its welcome return. A harsh bass synth sound and slap bass guitar permeate “Oudak Rannan,” which moves at a faster clip, with male chorus responses, scintillating oud breaks and a climax of percussion that could be either machine gun fire or frame drum abuse. This is the most desirable form of fusion for Fairuz.

With these early stylistic mergings, Fairuz and Ziad are successful around half of the time, mixing an elixir of Arabic pop with jazz, funk, and mild disco additives, deploying electric instrumentation, heard at its best down in the bass zone. They risked a dilution of Fairuz’s melancholy humor, but frequently gained a fresh form of then-contemporary framing energy.

Source: https://brooklynrail.org/2020/07/music/Fairuz-And-Her-Family-Fusions

Be the first to comment on "Fairuz and Her Family Fusions"